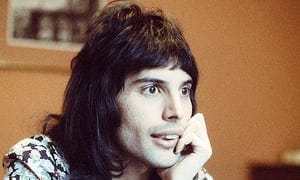

Note: This is a series about my mental health journey and how specific experiences led to my diagnosis of clinical depression and anxiety. For the full context, please read Part 1, the letter to my bullies, Part 2, the letter to my school friends,Part 3 and the letter to Farrokh Bulsara, if you haven’t already.

Part 4: In sickness and mental health, ’til death do us part.

Let’s get one thing out of the way: relationships are hard. If someone tells you that they are easy, especially if it’s a chick lit book about how two people have never fought during the course of their relationship, it’s an absolute bald-faced lie. Relationships are built on getting things out in the open with each other and it takes a lot out of each individual. We tend to be governed by fear about hurting the other person, whether it’s through our actions or our words. As human beings, we can be our own worst enemies.

When you add mental illness to this mix, it is a whole different ballgame.

My partner and I have been together for a little over three years (we started seeing each other in February 2016). We have pets together, we have seen each other through suicide attempts, we have been separated for months at a time, we have cried with each other, we have fought with each other, and we have also been abusive at times with each other. It’s not pretty, certainly. But it is the most real relationship either of us have been in. We feel lighter when we let out our frustrations with each other and we help each other in working through them. However, our individual mental health issues go back to way before we even knew that the other person existed.

The biggest anchor weighing me down mentally is that I tend to dismiss a lot of what is real and hope that if I ignore it for long enough, that feeling of dread will go away. Growing up, I wasn’t able to voice a lot of what I was feeling, mostly because I thought people didn’t care to listen to me whining and bitching about stuff that everybody goes through. So I retreated into my own mind; a lot like the main character of this film called Tideland.

In Tideland, Jeliza-Rose is an abandoned child with drug addicts for parents. The first night in a remote farmhouse, she loses her father to a heroin overdose, after also having lost her mother to a drug overdose. Rather than acknowledging her father’s death, Jeliza-Rose retreats into her own imagination and turns to her doll heads and a differently-abled brother-sister duo who end up enabling Jeliza-Rose’s delusions.

For me, it was the media that convinced me that nobody would ever truly love and accept me the way I was. If anyone I was in a relationship with tried to correct me or give me constructive criticism, I would spiral into my own thoughts and doubt my entire existence at times. Most importantly, I was convinced of the fact that relationships had to be perfect or it just wasn’t worth it. Oh boy, how utterly and completely wrong I was.

I would run away at the first sign of adversity in any relationship, burrowing myself either in my work, TV shows, or alcohol to stop me from even forming coherent thoughts about whether the possibility of me being wrong ever existed. It was the other person’s fault, I would tell myself. And then I would fully forget that I had fucked up at all during that relationship.

All that changed when I got together with NS. For the first-ever time in my life, I actually felt accountable for my actions. I was responsible for someone else’s feelings other than my own, because I finally realised that it wasn’t all about me. I still struggle with that sometimes. I often become this selfish asshole who just couldn’t give a shit about anybody around me except myself. It’s all about me, me, me, me, me. I hate that. I hate that the ugly side of me is selfish and self-involved, especially because I used to think that I cared only about others.

The truth is that I used to care about other people in the context of how they made me feel. And when you have anxiety, it’s like throwing gasoline at fireworks that are already destroying property. I am still scared of confronting tough situations sometimes. I act out of cowardice and I really don’t want to.

But the difference between life before NS and life with him is that I’m slowly learning how to forego myself completely at times when others need me and need my support. No, it doesn’t mean that I have lost sight of who I am. Ultimately, the only person who can truly take care of me is myself. But I know there are more than a few times when it is not about me at all.

NS, on the other hand, has never had trouble voicing his thoughts. However, his temper would reflect in the things he would say and do, which would often be incredibly hurtful to me, and ultimately both of us. Unlike me, he has never hesitated to admit that he is wrong. It takes him time to apologise, but he does it the right way.

Growing up, NS had similar experiences to mine. He said, and I quote, “I think there were people who hated me simply for the fact that I was still breathing.”

To hear that from the person who makes you have stars in your eyes is a shock, to say the least. You can’t fathom that people can’t love the person you love and you often wonder whether you’re doing right by them and loving them the right way.

Through NS’ biggest flare-ups, I have seen the root of them all; his burgeoning insecurities. Being told and reminded that you’re unlovable throughout your life tends to make you wonder whether the person you’re with actually loves you or not, and NS has wondered about that. A lot.

Has it been challenging to take him away from his insecurities and convince him that the love is real? Yes.

Has it been easy? Fuck no, we still cry like leaky faucets.

Has it been worth all the trouble? Fuck yes. I feel lighter every time I let it out with him. And I hope he does too.

Reading about dysfunctional relationships on social media can really fuck with your world view of what your relationships should be like, especially when both people have mental health issues. You wonder about what is objectively right and wrong when it comes to your actions and words. You worry that the people around you could disapprove of certain things in your relationship. You are scared to death that you, your partner, or both of you will be publicly shamed for the way you choose to conduct your relationship and the things you go through.

You know what I have learnt in the last hour, after crying and wondering whether I should be open about my relationship?

FUCK. THAT. SHIT.

Your friends and peers mean well and sometimes, leaning on your friends is essential. At the end of the day, human beings are social beings. Ultimately, you need to be able to strike a clear and understandable balance between your thoughts, how your partner is treating you, and what people you trust have to say about it. This is one of the reasons why therapy is an essential tool to help you figure out what could be holding you back in a relationship. It helps bring in a third-person perspective, with the least amount of bias, that you would not have been able to consider in the situations you have faced and the advice you have received earlier.

However, if you truly feel like you are unsafe in a relationship, reach out to someone and seek help. There have been people who have been driven to death by a relationship and that is not okay (please watch the video; TW: suicide, physical abuse, stalking). There is a huge difference between riding out the constant frustrations of a relationship and feeling like your days are numbered because of a relationship.

As human beings, we are all learning. And as mental health patients, NS and I are learning how to live, really. It’s a long and unwieldy road, but I can’t imagine going down it with anybody else.